With a little help from a colleague, Agency by Design researcher Jessica Ross was empowered to use some basic electronic materials to power an LED light and a small speaker with a 9V battery.

It is hard to travel long among young makers without stumbling across circuits. TinyCircuits, Snap Circuits, Squishy Circuits, breadboards, soldered circuits… almost everywhere you look, circuitry design is happening in classrooms, at home, and in after school settings.

Students at Park Day School building props for student written plays with LED circuits.

I recently had the privilege of talking to a variety of young circuit designers eager to talk about what they were working on. However, since I didn’t know what a potentiometer does and I had never soldered in my life, I began to feel that my questions were becoming tedious after an eleven year-old had patiently explained to me how electrons move through wires for the third time. AS a result, I decided that it might be time to bridge the gap (if ever so slightly) in my circuit building knowledge, so I decided to learn by doing.

Developing a Sensitivity to Design by Looking… and Doing

The Agency by Design research team has thought a lot about the ways to encourage a sensitivity to design through classroom practices. We have engaged learners both young and old in exercises that require careful looking, considering the parts, the purposes, and noticing the complexities of objects or systems.

A student designed Medusa headdress for an upcoming school play—complete with flashing LED snake eyes!

Simple objects, like a light for a bike helmet for example, have a variety of parts, a specific purpose, and design elements that were employed to meet the needs of a variety of users. We can observe many of these elements through a process of careful looking, but what about actually understanding something like the circuit design involved in making an LED light flash when connected to a battery—the basic function of a bike helmet light before the carefully designed outer shell is added?

I can promise you this; it takes a bit more time than ordering the bike helmet light online. For me, it took an entire weekend.

Diving into Circuit Design

Before I dove headfirst into tinkering with circuit design, I decided I needed a guide. So, I asked my friend Rob to help me out. Rob has a PhD in Optics and does something with mirrors on big telescopes, but more importantly he is a tinkerer by nature: carpentry, photography, making the perfect cup of coffee… are all opportunities for exploration for him.

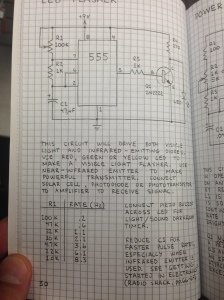

I told Rob I wanted to start small and I wanted to see in person what my options were, so he brought me to a local electronics supplier where we skimmed through the electronic project manuals until I settled on one entitled Timer, Op Amp & Optoelectronic Circuits & Projects by Forrest M. Mims III. After I determined my first project—constructing my very own breadboard circuit—just because I got excited about some other options, we picked a second project. Despite my enthusiasm, Rob and I decided it was prudent to stop there.

Early on, Rob announced he would only be my guide. He would not touch any of the pieces, but would help me find answers to questions I had if I needed them. In his role as my guide, Rob provided just-in-time learning and a wealth of content knowledge—I was in good hands.

First, Read the Manual

While I had a compassionate flesh and blood guide in the form of Rob, I also had the Mims book as a printed word guide I could follow. Once home, I felt pretty confident upon opening this text. The project guide read like a cookbook: a brief description of the item I would be making, a list of ingredients (some with precise measurements), step-by-step instructions, and even a diagram. I wasn’t daunted by the fact that this circuitry cookbook was in a foreign language to me; in the past I have learned words in several other languages because I was motivated by food and willing to look up new terms.

My field guide: Timer, Op Amp & Optoeloctronic Circuits & Projects by Forrest M. Mims III.

Admittedly, at first, my learning curve was slow and my fear of failure was high. I could easily repeat back how currents moved and the rationale for how a resistor might react in contrast with a capacitor. But what if the beacon of light never flashed when I was all done?

I opened the myriad of tiny packages and laid my shiny new breadboard on the table and started to use the grid to build the circuit. As I followed the recipe, I prepared materials by trimming wires, I learned to read the new language, I began to understand the relationship between the components, and I gained confidence. Finally, the moment of truth! I plugged the 9-volt battery onto the board and—epic failure. No light. And when Rob (as a safety measure) touched the 555-circuit he got a nicely scorched finger.

I went back through every step, rechecked each tiny bag for instructions. Was my intermittent wiper on the right grid number? Were wires crossed? In fact, I soon figured out that in my excitement I had erroneously used the 386-audio circuit (a piece for project #2) as the base of my design as opposed to the 555. A simple enough correction and my LED light flashed dutifully.

Reflecting on the Journey

My total immersion circuitry project yielded much food for thought including a bunch of new questions about what learners, teachers, and schools—or other learning environments—need to consider when designing learning opportunities like this.

One of my questions was about information and the role a guide can play in new learning experiences. A wonderful question that comes from our colleagues at the National Gallery of Art around art history education is: What is the role of information? When do we offer it, how much, for which learner, and with what sort of learning experience? Would I have arrived at the same understandings and genuine interest in gathering more information from reading an article about simple circuits, or attending a short lecture?

My circuitry experience also surfaced questions I had about other issues to consider: engagement, learning by doing, having the opportunity to fail and try again, learning from text, the web, and one’s peers (sometimes simultaneously), and having fun while learning—to name a few. I am still thinking about these big questions as my LED light flashes—and while I am planning my next project.

What should I explore next? Computer Science Education Week just passed, but it is never too late, right? So, maybe some coding?

Reblogged this on David Lee EdTech.

Pingback: Articles of Interest December 20, 2013 « National Creativity Network

Jessica, what timely post. I could have written this after my introduction to greater understanding of circuits during the last few weeks. (Except that I’m the one who ended up with a scorched finger after mixing up the positive and negative end of the temperature sensor on Circuit 7). Like you, I’ve decided to stop watching and coaching amazing learning experiences where others “make” and get down and dirty into the actual making it myself. My lack of understanding of circuits really shed light on some of the experience gaps some of us have. In my case, I think it was due to 1) gender – grew up in a family of 5 girls where most science experiments were conducted in the kitchen (baking) 2) lack of opportunity to gain deep understanding of basic science concepts (probably due to my inequity in my elementary education where elementary teachers thought all subjects, and most likely favored the ones they really understood themselves. I documented my circuit experience here. http://makecreateinnovate.blogspot.com/2014/02/i-see-light-exploring-world-of.html

I, too, was fortunate enough to have a guide/mentor who stood back and chimed in ONLY when I reached a block, and who patiently responded to my grilling him until I gained my own understanding of what has happenings with the flow of energy in each circuit.

I’m about to post a part two that includes my final project where we remixed code from various sketches to create our own invention.

The classic 555 timer could be used in so many ways. It is a legend by itself. Thanks for sharing your story!

Hi John,

While my friend was introducing me to this world, it was expressed to me quite emphatically that there were, “WHOLE BOOKS published on the 555 Timer!” I haven’t quite delved in that deep yet, but I do appreciate the possibilities.

Glad you enjoyed the post! Jessica